Looking back on ten years of community-based monitoring

An interview with Chelsea Lobson

August 27, 2025

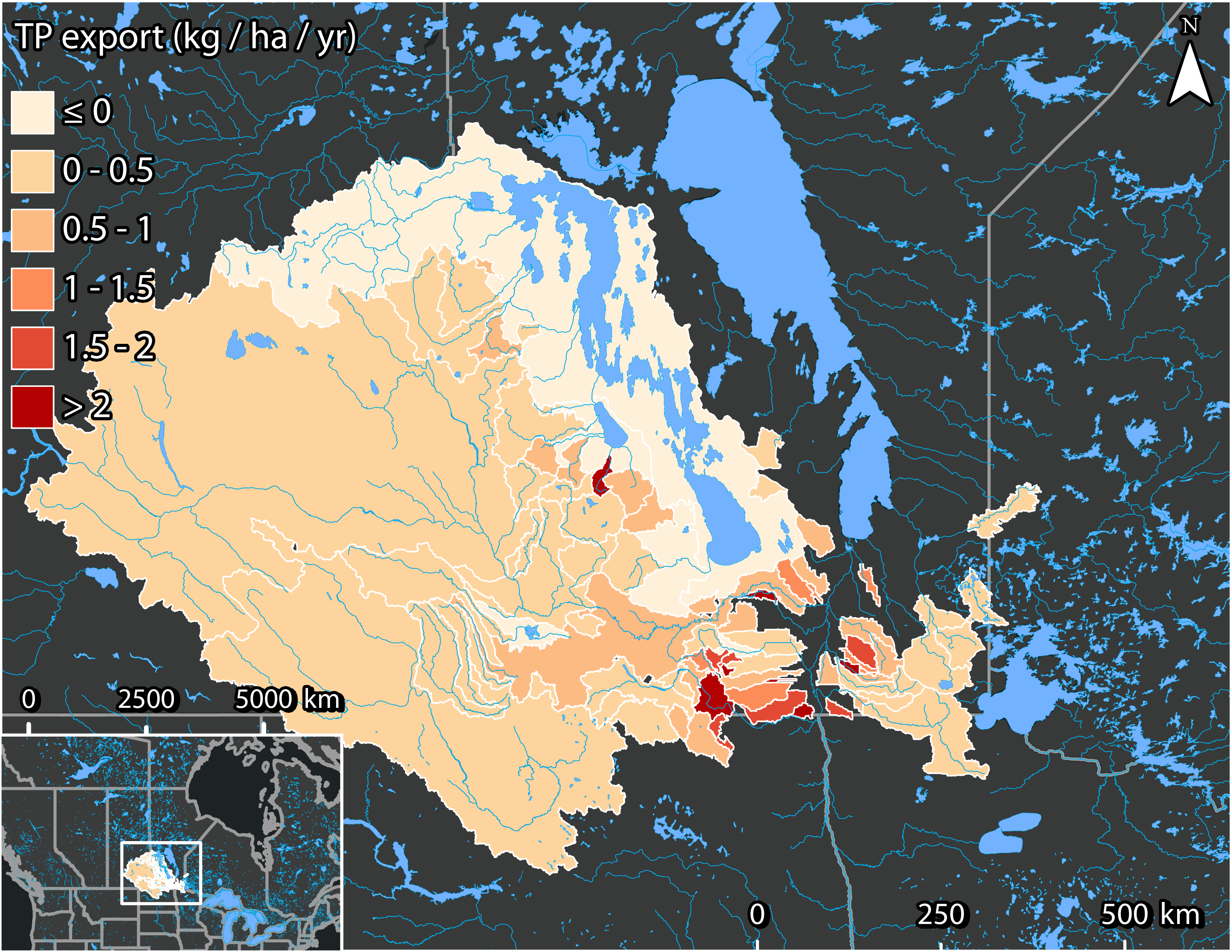

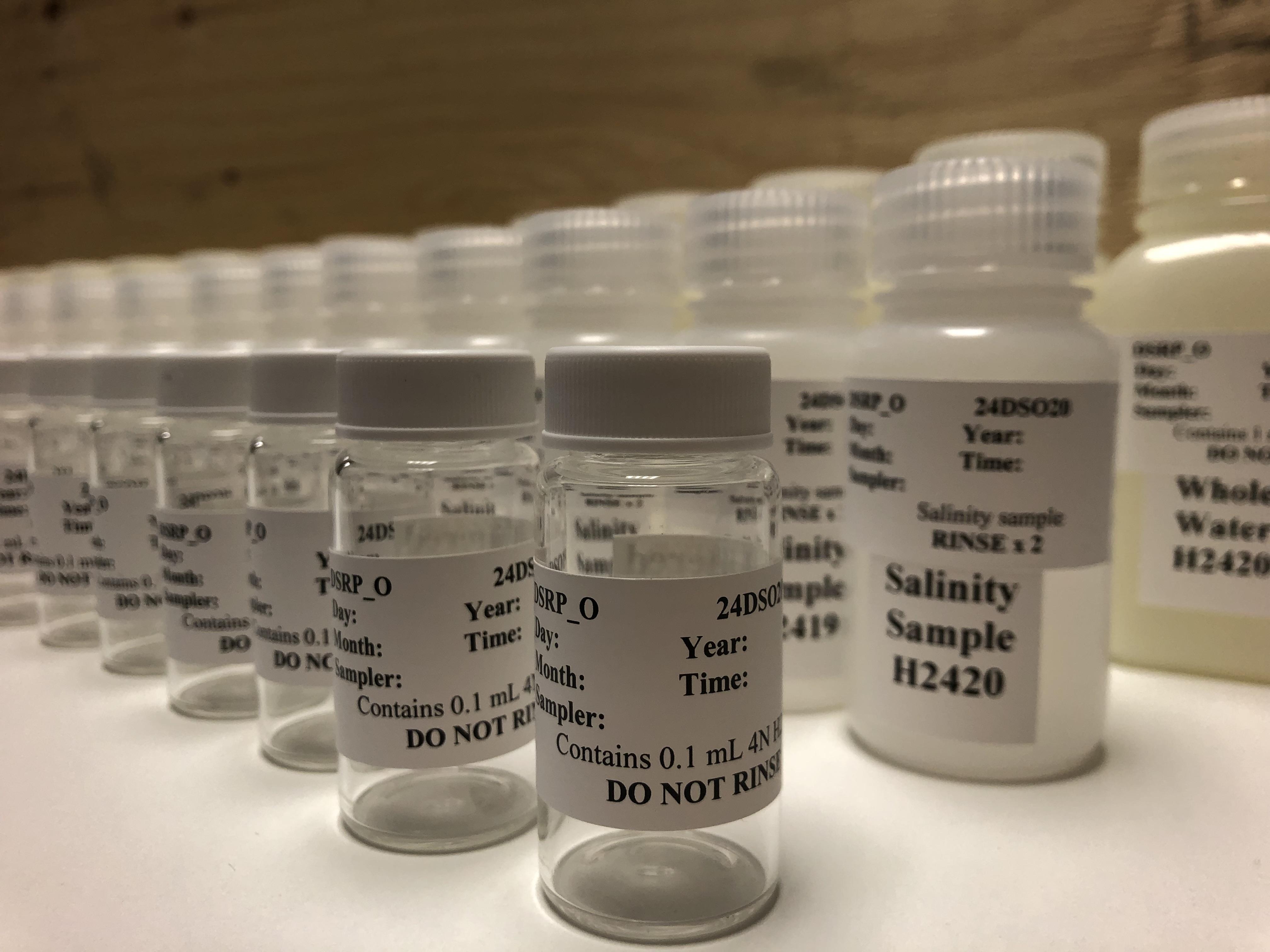

The Lake Winnipeg Community-Based Monitoring Network (LWCBMN), coordinated by LWF, is a network of volunteers and watershed district partners collecting water samples for phosphorus testing in the Lake Winnipeg watershed. Decades of ecosystem science at the Experimental Lakes Area (now known as IISD-ELA) shows that to reduce algal blooms on Lake Winnipeg, the excess phosphorus flowing into the lake from the watershed must be reduced. In order to do that, scientists and policy makers need to know where that phosphorus is coming from. This is where LWCBMN data is needed.

Who are you and what is your role at LWF?

I am Chelsea Lobson, LWF’s Programs Director. I joined the organization as a Program Coordinator in 2017, right after the launch of LWCBMN in 2016. As the program has grown, so has my role. I now lead LWF’s programs team—made up of a Water Data Specialist, Program Coordinator, and several co-op students—while also liaising with academic and government researchers.

I remember in my job interview back in 2017, I told the interviewers that I was passionate about doing science that informs policy. Now, I’m proud that my role has become exactly that – ensuring that LWCBMN data is being used to inform policy and management decisions for Lake Winnipeg. It’s been rewarding to see that vision realized.

How did the network come to be?

One of the challenges with addressing phosphorus loading to Lake Winnipeg is the size and multi-jurisdictional nature of the watershed. The watershed stretches from the Rocky Mountains almost to Lake Superior, and dips into four American states. Our science advisors noticed that efforts to improve the health of Lake Winnipeg were spread thin over that vast area. There was a lack of information about how to target efforts effectively, and our advisors thought a community-based monitoring network could address this.

With community volunteers sampling throughout the watershed, we can generate the high-resolution data needed to target resources and action to the areas that are contributing the most phosphorus – areas that we call phosphorus hotspots.

The most distinctive feature of LWCBMN, compared to more centralized monitoring programs, is the network of on-the-ground volunteers and partners. In the Lake Winnipeg watershed, most phosphorus runoff occurs during the spring melt and after large storms. Other monitoring programs couldn’t sample effectively during these high flows, because of the logistical challenges of travelling to many dispersed sites in relatively short periods of time. This is why having on-the-ground volunteers and partners is key to the success of LWCBMN and why we can generate such high-quality data.

Photo: Kanak Kulhari

Photo: Fallon Moreau

Photo: Fallon Moreau

How did you first get volunteers onboard with the idea of community-based monitoring?

Our science advisors had a strong vision of how volunteers could help generate this data. But we were still worried about whether volunteers would even be interested in participating in something like this.

We had many conversations about how to attract volunteers. What could we give them to keep them engaged?Gifts or participation medals, t-shirts (I still think this could be fun!) or hats? Ten years later, it’s clear that community members are just as concerned as us about water quality – what they were looking for was a hands-on way to get involved. The network gave them just that!

What we’ve heard from our community repeatedly is that they want to be part of a larger collective solution. They want to contribute to a greater, coordinated effort to improve water quality for Lake Winnipeg – and they want to know what the data is telling us. It’s that desire to contribute to something bigger—and we aim show them just how much their efforts matter.

To paint a picture of how community connections are made: I started with LWF as Program Coordinator in January 2017 and recruited some of our first volunteers by early March. I planned to train a group in Morden, Mb., when a freezing rainstorm hit—but with the spring melt approaching, I was determined to still make it there. I set out despite the rain, quickly realized I was out of my depth, and pulled into a gas station. Thankfully, one of the volunteers came to my rescue in a more weather-ready vehicle, and I ended up doing my first training at the Brunkild Esso.

It wasn’t the ideal “in-field” session, but it worked—and it’s moments like this that show how LWCBMN is rooted in grassroots, real-world connection. Volunteers see how they fit into the bigger Lake Winnipeg story and find purpose in their role as part of the larger effort.

How is the data being used to help Lake Winnipeg?

It’s really neat to see how this data is now being used by researchers and government scientists to target persistent phosphorus hotspots. For example, LWF partners with a group of scientists from the University of Winnipeg – led by Drs. Darshani Kumaragamage and Nora Casson – who are studying phosphorus runoff from flooded soils. They used LWCBMN data to select field sites that were within hotspots. This approach ensures that their research is relevant, because it takes place in the areas that contribute the most phosphorus.

The obvious question that gets asked when someone sees our phosphorus hotspot maps is, “What is going on in those areas that makes them a hotspot?” and, well, we are wondering the same thing! So, we are working with our science advisors to analyze our phosphorus data alongside land-use data, in order to connect what is happening on the land with what we are measuring in the water. This new analysis will contribute to our understanding of what makes a hotspot a hotspot.

Has the network changed over time? If so, how?

For the first decade of LWCBMN, we focused on building trust with government and academics by sharing our methods and our data widely. We wanted to demonstrate that community-based monitoring could build a robust long-term data set to identify persistent phosphorus hotspots.

Now, ten years in, we’ve succeeded at those goals – we have built trust with key data-users, and our data shows persistent phosphorus hotspots. There is a lot of momentum behind the program, and we are ready to focus this next phase on incorporating the data into policy and decision-making processes for a healthier Lake Winnipeg.

Currently, we are collaborating with three different federal government groups who are using LWCBMN data to target action for phosphorus reduction. The tone of our conversations with high-level officials has notably shifted. Where we once spent time defending the quality of community-generated data, we’re now being asked how the data can be used to address phosphorus hotspots, which is exactly the conversation we want to be having!